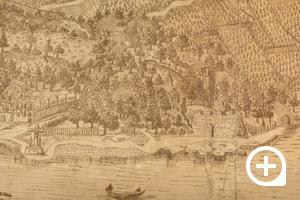

Townscape of 1742

Townscape

With the portrayal of Bad Salzig in the east up to Jakobsberger Hof in the west it maps an area of around ten kilometres. Even though some buildings are represented in a very detailed way, the main intention was presumably to depict the town forest. Several clearly defined landmarks lend weight to this argument, of which one can be seen in the museum today, next to the townscape.

Despite this limitation, the townscape invites you not only to look at the town, but also to look for chapels, landmarks, wayside crosses or 26 different types of ship on the Rhine.

The townscape was thoroughly restored in 1985.

Goswin Klöcker came from Koblenz and married Anna Katharina Maser on the 23 January 1731 in Boppard. By profession he was an imperial notary and lawyer at the Boppard Law Court.

Exactly when he finished the townscape is no longer known. It can be assumed though that he had been tasked to do it by the town.

The Elector’s Castle

Audio

Even in the middle of the 18th century, a part of the castle still served as a customs house for the Trier area; other parts are designated as the Elector’s Castle. Today one of the cultural centres of Boppard can be found here in the museum.

The Royal Court

Audio

Already by the middle of the 18th century only the remains of the Royal Court existed. A tower without a roof and a crenellated wall overlooking the Rhine are the remains of the site, from where Richard of Cornwall besieged Boppard in 1257.

St Severus

Audio

Central to the middle of the picture, and almost dominating it as much as the Elector’s Castle, is the parish church of St Severus (82), which was consecrated in 1237. It dates back to an early Christian shrine, which was built in the fifth/sixth century by using buildings of the Roman Baths.

Eaglestones

Audio

The so-called ‘eaglestones’ marked the whole course of the border around Boppard. They are represented on the townscape as disproportionally large, presumably so that they could be noticed immediately as boundary markers. They bear as a symbol the imperial eagle and thus point to an important, and for the Boppard town history remarkable, piece of evidence: they mark the border of the narrow Boppard treasury, as it had been transferred to the Archbishop of Trier and Elector, Balduin of Luxembourg in 1312.

St Martin

Audio

The convent, situated outside the city walls, dates back to a chapel, donated to St Ursula’s convent in Cologne in around 915. In 1425 reference was made to a small convent of the Beguines, which later became a convent for the Franciscan Sisters in 1485. Within these walls lived and worked the physician, ethnologist and Japan researcher Philipp Franz Freiherr von Siebold from 1847 to 1853.

Floor tiles

The floor tiles come predominantly from the royal court, an important building at the western entrance to the town. They show an eagle, looking to the right (K II 0016), a circle with a star-shaped blossom with eight petals (K II 0019), a lion pacing to the right (K II 0014, K II 0015) and other decorative elements.

The floor tiles come predominantly from the royal court, an important building at the western entrance to the town. They show an eagle, looking to the right (K II 0016), a circle with a star-shaped blossom with eight petals (K II 0019), a lion pacing to the right (K II 0014, K II 0015) and other decorative elements.

The royal court received its name after kings had stayed there during their visits to Boppard on various occasions. The last important king of the Staufer period, Frederick the Great (1212–1250), alone visited the royal court in Boppard at least five times. The remains of this court can be seen on the large townscape (Lit.: Mißling, Heinz E. (Ed.): Boppard – Geschichte einer Stadt am Mittelrhein. Volume 1. Boppard 1997, p. 136 et seq.)

At this time of the so-called interregnum of the Holy Roman Empire, Boppard was of great significance as the north-western outpost of the Staufer Dynasty and was often fought over as a result. Richard of Cornwall is said to have besieged the town in 1257 from the royal court.

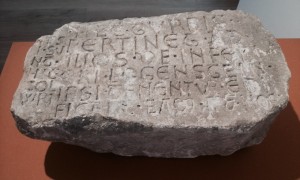

Stone with legal inscription

Its inscription reads

‘HEC TURRIS / PERTINET AD / ILLOS DE INFERI / ORI LOGENSTEIN / IPSI TENENTUR EDI / FICARE EAM P(RO)PT(ER) HOC / / IPS / I SV / NT / HIC / COL / WR I’.

The English meaning is:

‘This tower has been assigned to those people of Niederlahnstein. They are obligated to maintain it; therefore they are freed of tax here.’

With the aid of the text, the stone was dated to the first half of the 12th century. A similar stone can still be found today in Haus Burggraben 4. It refers to tower 16 of the old town fortifications and concerns the citizens of Oberwesel.

‘The inscription is one of a small number of traditional medieval legal inscriptions mostly from the 12th and 13th centuries, which contained fundamental privileges or benefits for the citizens and residents of a city or for those trading with them and therefore implemented as a monument in the place where the privileges were granted and made publically visible. This particular inscription is one case of a particularly rare hybrid, which imposed a maintenance obligation of a tower in the town walls on newcomers to the town and gives them in return tax exemption.

Presumably this privilege does not deal with exemption of the very old and important Boppard Empire toll, which could only be granted by the King as the customs official, but rather dealt with the release from the market tax, which the council of the former imperial city of Boppard could decree itself. The exact circumstances of this astonishing legal relationship between the citizens of Boppard and those of Niederlahnstein, or Loginstein, as it was called in 1100, a few kilometres up the Rhine at the mouth of the river Lahn, are unknown. Yet one reason for this agreement could be that maintenance of the town wall with its presumably 28 towers, dating to the Late Roman times, was not possible for the town of Boppard through its own means, despite a growing population in the 12th century. This inscription, together with a similar one for Oberwesel provides an important indication of the early beginnings of the repair and restoration works on the town fortifications, which were at that time 900 years old. Up until now, it had been assumed that these rather took place in the 13th century. The early dating of the inscription, carried out here for the first time, is supported by the observation of archaeologists, that the demolition of the northern town wall in favour of an extension on the Rhine side, had been started at the latest when the nave in the Church of St Severus was built in the first half of the 13th century. As the inscription deals with tower 25, the last tower before the north-western corner of the town wall, it is not clear at which point in time it was affected by these reconstruction measures.’

Find more on the stone at DEUTSCHE INSCHRIFTEN ONLINE

Boppard Sömmer

A ‘Sömmer’ is a measure of capacity, with which grain could be measured, for example. The Boppard ‘Sömmer’ was found in 1864 whilst work was being carried out on the second floor of the north tower of the Church of St Severus and came to the museum in 1930 as a permanent loan. The Sömmer is predominantly made of bronze and has two tapered handles on the sides above and below. Its three feet are formed as animal paws, which protrude with a small, thin bar into the body of the receptacle. This could be enlarged with two rings. Its capacity is originally 24.975 litres, or 28.890 litres after the two enlargements. The external wall of the vessel is engraved with an inscription encircling it, in raised capital letters in gothic script:

A ‘Sömmer’ is a measure of capacity, with which grain could be measured, for example. The Boppard ‘Sömmer’ was found in 1864 whilst work was being carried out on the second floor of the north tower of the Church of St Severus and came to the museum in 1930 as a permanent loan. The Sömmer is predominantly made of bronze and has two tapered handles on the sides above and below. Its three feet are formed as animal paws, which protrude with a small, thin bar into the body of the receptacle. This could be enlarged with two rings. Its capacity is originally 24.975 litres, or 28.890 litres after the two enlargements. The external wall of the vessel is engraved with an inscription encircling it, in raised capital letters in gothic script:

Vme ein rechte beshedieit So vordi dusse svmeri bereit ume rechte sachge so dadi mirse machi.

That means

For the sake of legal clarity, these Sömmer were produced; for the sake of a just verdict in the event of dispute we had them made.

The external wall of the vessel is otherwise smooth apart from four small coats of arms, depicting eagles, with one of them marking the beginning of the text.

The formation of the letters and the fact that the text was written in late Middle High German allows the vessel to be dated to the first third of the 14th century. As Boppard had its own currency and its own measurement at the time of Imperial Cities and later at the time of the Electors of Trier, the town must have commissioned it to be made. That would also explain the frequent use of the town’s coat of arms. The place it was found also speaks in favour of this theory, as it was discovered in a room in which supposedly the town archives were kept and certainly the town treasury where cash was stored.

It remains unclear whether we are dealing with the town’s standard measure or a functional measure. Also where exactly it was used and by whom is today no longer known. With a weight of 21 kilograms it will have had a fixed location, and not have been carried on occasion to the market, for example.

Find more about the Boppard Sömmer on DEUTSCHE INSCHRIFTEN ONLINE

The Portal

The passage to the next room is through a portal: An ornate room door from 1603. It originates from the Schaaf’s house built in the early 17th century. The house was demolished in 1896. It used to stand at the corner Seminarstraße / Ordensritterstraße. The door has been part of the museum collection since 1935.